Coop, Actually – Part 1 (Kathy – Brussels – January 2026)

Version en français ci-dessous – Nederlandse tekst hieronder

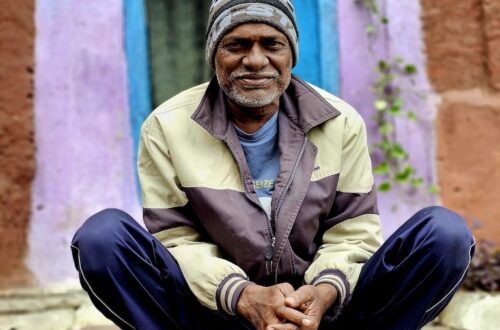

What India Makes Visible — and Europe Often Doesn’t

Mandrem, Goa. A tiny town by the sea: a few streets, palm trees, small shops, the familiar buzz of scooters. And then, on the corner of a wall, a simple sign, almost ordinary: Candolim Urban Co-operative Credit Society Ltd.*

This is the second photograph in my book How Do Cooperatives Create Prosperity for All? (if you would like to purchase it: https://tally.so/r/w20YRM). I chose it because it captures something essential, without speeches or slogans. It shows just how visible cooperative identity is in India.

There, the word cooperative is not tucked away. It is displayed. It appears in names, on façades, on menus, across everyday landscapes. It is not only a legal status or an economic model: it is a form of belonging, a social reality. In many contexts, it is also a practical way to access credit, build economic autonomy, and provide collective security.

Belgium, by contrast, is an interesting—almost paradoxical—case. The country has a long and structurally significant cooperative tradition. Cooperatives are active, among other sectors, in energy, agriculture, retail, finance, housing, culture and construction.

In several areas, new citizen-led cooperatives have emerged in recent years, particularly in the field of energy. They enable local residents to invest collectively in projects and to take part in their governance.

Some cooperative enterprises play a major role in daily life, without their cooperative status always being made explicit. Well-known examples include Multipharma, Crelan, and the P&V insurance group.

The issue, then, is not whether cooperatives exist in Belgium, but how easily they can be identified in public space—even by those who rely on them or participate in them.

Why this lack of visibility?

It is not only a matter of communication. It is cultural. In Europe, the cooperative enterprise is still too often placed in a secondary category, perceived as an alternative model rather than as a fully-fledged economic force.

In countries such as India, by contrast, cooperatives are central actors in economic development. Some of the country’s largest organisations are cooperatives. One of the most striking examples is Amul, the giant dairy cooperative regularly highlighted by the International Cooperative Alliance as having one of the most significant economic impacts relative to the size of its national economy. In fact, my book includes an entire chapter dedicated to Amul, precisely because its scale and member-based structure offer such a compelling illustration of what cooperative enterprises can achieve.

This relative lack of visibility in Europe has recently prompted initiatives such as the Coop campaign launched in France by COOP FR. The idea is straightforward: to encourage cooperatives to include the word “Coop” explicitly in their name, so they can be recognised at first glance, distinguished from capital-owned firms, and clearly associated with an ecosystem based on democracy, solidarity and collective ownership. https://www.entreprises.coop/promouvoir-le-modele

The campaign also promotes practical tools, such as adopting the .coop domain, which helps make cooperative identity more legible online as well.

This is not insignificant.

To name something is to make it visible. To name it is to claim it. To name it is to allow citizens to recognise what they are truly supporting.

*Note: In India, many cooperatives are established with limited liability. Cooperative law therefore requires the term “Limited” to appear in their official name (Co-operative Societies Act, 1912, Section 10).

Wat in India zichtbaar is, en in Europa veel minder

Mandrem, Goa. Een piepkleine kustplaats: een paar straten, palmbomen, winkeltjes, het vertrouwde gezoem van scooters. En dan, op een muur om de hoek, een eenvoudig bord: Candolim Urban Co-operative Credit Society Ltd.*

Dit is de tweede foto in mijn boek Coöperaties bouwen aan een betere wereld (als u het graag wil aanschaffen: https://tally.so/r/m6ozbY). Ik koos ze omdat ze zonder omwegen toont hoe zichtbaar coöperaties in India zijn.

Daar wordt het woord coöperatie niet verhuld. Het staat op gevels, in namen, in het straatbeeld. Het is een herkenbare organisatievorm, geen voetnoot. In veel contexten betekent het ook iets heel concreets: toegang tot krediet, meer economische zelfstandigheid, een vorm van collectieve zekerheid.

België is in dat opzicht een interessant, bijna paradoxaal geval. Ons land heeft een lange coöperatieve traditie. Coöperaties zijn o.a. aanwezig in energie, landbouw, distributie, financiën, wonen, cultuur en bouw.

De voorbije jaren zijn er nieuwe burgercoöperaties bijgekomen, vooral in de energiesector. Ze maken lokaal collectieve investeringen mogelijk, met inspraak van leden in het bestuur en de besluitvorming.

Daarnaast zijn er grote coöperatieve ondernemingen die een vaste plaats innemen in het maatschappelijke leven, zonder dat hun statuut altijd expliciet zichtbaar is. Multipharma, Crelan en verzekeringsgroep P&V zijn bekende voorbeelden.

De vraag is dus niet of coöperaties bestaan in België. De vraag is hoe snel ze als coöperaties herkenbaar zijn — ook voor mensen die er klant zijn of lid van zijn.

Waarom blijft die zichtbaarheid beperkt?

Dat heeft niet alleen met communicatie te maken. In Europa wordt de coöperatieve onderneming minder vanzelfsprekend als volwaardig bedrijfsmodel gezien naast kapitaalvennootschappen.

In India ligt dat anders. Coöperaties nemen er een prominente plaats in binnen grote sectoren van de economie. Een van de bekendste voorbeelden is Amul, de gigantische zuivelcoöperatie die door de Internationale Coöperatieve Alliantie regelmatig wordt genoemd als een van de coöperaties met de hoogste ratio tussen omzet en het BBP per inwoner. In mijn boek is een volledig hoofdstuk aan Amul gewijd, precies omdat hun schaal en ledenstructuur scherp laten zien wat coöperatief ondernemen kan betekenen.

Net die relatieve onzichtbaarheid in Europa ligt mee aan de basis van initiatieven zoals de campagne Coop , gelanceerd in Frankrijk door COOP FR. Coöperaties worden aangemoedigd om “Coop” expliciet in hun naam op te nemen, zodat ze onmiddellijk herkenbaar zijn en zich duidelijk onderscheiden van kapitaalgedreven ondernemingen.

De campagne wijst ook op concrete middelen, zoals het gebruik van het domein .coop, om die identiteit ook online zichtbaar te maken.https://www.entreprises.coop/promouvoir-le-modele

Dat is geen detail.

Zonder naam geen zichtbaarheid. En zonder zichtbaarheid geen plaats in het economische verhaal.

*Nota: In India zijn veel coöperaties opgericht met beperkte aansprakelijkheid. De wetgeving verplicht daarom dat het woord “Limited” deel uitmaakt van hun officiële naam (Co-operative Societies Act, 1912, Section 10).

Ce que l’Inde rend visible, et l’Europe beaucoup moins

Mandrem, Goa. Une toute petite ville en bord de plage, quelques rues, des palmiers, des échoppes, le bruit familier des scooters. Et puis, au détour d’un mur, une enseigne simple, presque banale : Candolim Urban Co-operative Credit Society Ltd.*

C’est la deuxième photo de mon livre “Comment les coopératives créent de la prospérité pour toutes et tous” (si vous souhaitez l’acquérir : https://tally.so/r/wAZYal). Je l’ai choisie parce qu’elle dit quelque chose d’essentiel, sans discours ni slogan. Elle dit à quel point l’identité coopérative, en Inde, est visible.

Là-bas, le mot coopérative ne se cache pas. Il s’affiche. Il s’inscrit dans les noms, sur les façades, sur les menus, dans le quotidien. Il ne s’agit pas seulement d’un statut juridique ou d’un modèle économique : c’est une appartenance, une évidence sociale. Dans de nombreux contextes, c’est aussi un outil concret d’accès au crédit, à l’autonomie économique, à une forme de sécurité collective.

La Belgique est un cas intéressant, presque paradoxal. Le pays a une tradition coopérative ancienne, structurante. Les coopératives y sont présentes e.a. dans l’énergie, l’agriculture, la distribution, la finance, le logement, la culture et la construction.

Dans plusieurs secteurs, de nouvelles coopératives citoyennes se sont développées ces dernières années, notamment dans l’énergie. Elles permettent à des habitant·es d’investir collectivement dans des projets locaux et de participer à leur gouvernance.

Dans d’autres domaines, certaines entreprises coopératives occupent une place importante dans la vie quotidienne sans que leur statut soit toujours explicitement mis en avant. Des coopératives bien connues comme Multipharma, Crelan ou le groupe d’assurances P&V en sont des exemples.

La question n’est donc pas celle de l’existence des coopératives en Belgique, mais de leur identification immédiate dans l’espace public, y compris par celles et ceux qui y recourent.

Pourquoi cette invisibilité ?

Elle n’est pas seulement une question de communication. Elle est culturelle. En Europe, l’entreprise coopérative est actuellement souvent reléguée dans un registre secondaire, perçue comme alternative plutôt que comme une force économique structurante.

À l’inverse, dans des pays comme l’Inde, la coopérative est un acteur central du développement économique. Certaines des plus grandes organisations du pays sont coopératives. L’exemple le plus frappant reste Amul, immense coopérative laitière régulièrement mise en avant par l’Alliance Coopérative Internationale comme l’une des coopératives ayant l’impact économique le plus massif par rapport à la taille du pays.

Ce manque de visibilité en Europe a récemment conduit à des initiatives comme la campagne Coop lancée en France par COOP FR. L’idée est simple : encourager les coopératives à intégrer explicitement “Coop” dans leur nom pour être identifiables au premier coup d’œil, se distinguer des entreprises à capitaux, et afficher leur appartenance à un écosystème fondé sur la démocratie, la solidarité, la propriété collective.

La campagne propose également des outils concrets, comme l’adoption du domaine .coop, pour rendre cette identité plus lisible, y compris en ligne. https://www.entreprises.coop/promouvoir-le-modele

Ce n’est pas anodin.

Nommer, c’est rendre visible. Nommer, c’est revendiquer. Nommer, c’est permettre aux citoyen·nes de reconnaître ce qu’iels soutiennent réellement.

*Note : En Inde la législation coopérative impose l’ajout du terme « Limited » dans le nom officiel (Co-operative Societies Act, 1912, art. 10).