KGB, KBR, FBI, MI6 (Kathy – Brussels – January 26)

English version below – Nederlandse versie hieronder

KGB, KBR, FBI, MI6, non ce n’est pas le line-up du dernier James Bond.

Si comme moi vous avez une large expérience en services secrets, trois lettres vous auront fait tilter.

KBR ! Mais c’est quoi ce truc ?

KBR, c’est un service de protection rapprochée pour les trésors écrits de l’humanité. Bon OK, du minuscule Royaume de Belgique.

Bruxelles, capitale de la Belgique, hoofdstad van België, Hauptstadt von Belgien, recèle de nombreux joyaux. Certes, nous abritons un palais royal, une Grand Place unique au monde soigneusement gardée par Saint-Michel, de nombreux bistrots, le musée de la BD, un conservatoire de musique en piteux état, un palais d’une justice qu’on voudrait préserver à tout prix dans un monde qui semble en avoir oublié le goût, des frites, des moules, des bières, du chocolat et une bibliothèque monumentale perchée sur le Mont des Arts.

Mais d’où viennent ces trois lettres ? Histoire belge : chez nous on aime mélanger les genres, les langues et les saveurs. “Historiquement, le nom KBR est la contraction de deux appellations bilingues : ‘Koninklijke Bibliotheek’ et ‘Bibliothèque royale’…. De par le passé, elle reçut une multitude d’appellations comme Albertine, La Royale, BR, KBR, KB, Bibliothèque royale, etc.” (Extrait du site : https://www.kbr.be/fr/histoire-de-kbr/).

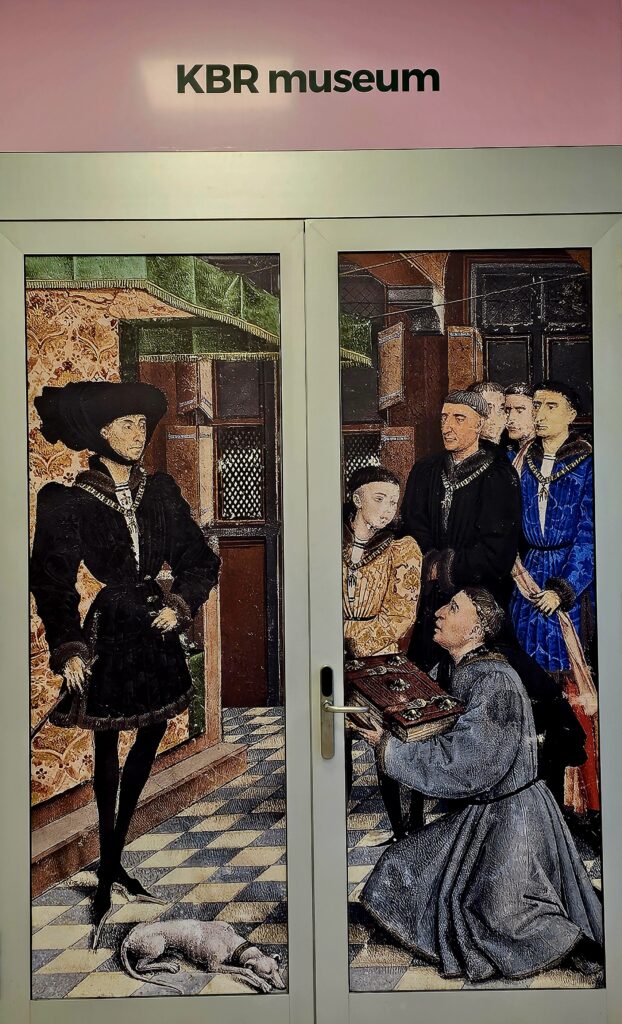

Comme souvent dans notre humble royaume, les ducs de Bourgogne et la France se mêlent de tout. Cette histoire commence au XVe siècle quand ces nobles personnages ont la bonne idée de rassembler 900 ouvrages précieux pour dominer le monde de la connaissance, une mission du genre “MANUSCRITS ÉTERNELS” — une collection unique de volumes enluminés. C’est ainsi que naît la librairie des ducs de Bourgogne qui abrite un trésor inestimable à la mort de Philippe le Bon. Vous l’aurez compris, l’ancienne Librairie des ducs de Bourgogne, c’est la crème de la crème médiévale. Notre noyau dur. Notre Graal visible encore actuellement au XXIe siècle au KBR museum (https://www.kbr.be/fr/museum/).

On pourrait faire un saut quantique, mais ce serait dommage car l’affaire se corse, riche en rebondissements, en appâts du gain, en alliances et mésalliances historiques.

En 1559 : Philippe II rassemble tous les ouvrages en sa possession au Palais du Coudenberg. Dès lors, cette collection prend le nom de Bibliothèque royale.

Mais en 1731 un incendie ravage ce fameux Palais du Coudenberg. Heureusement, nos ancêtres ont évacué les manuscrits in extremis. Bravo les gars.

En 1746 les Français débarquent et occupent Bruxelles. Ils “empruntent” nos trésors direction Paris. Il faudra attendre 1770, soit 24 ans plus tard, pour qu’une partie d’entre eux nous soit restituée.

Les autres ? Disons qu’on préfère ne pas en parler ici pour ne pas envenimer nos relations avec Macron.

En 1754, premier déménagement clandestin : les collections trouvent refuge dans la Domus Isabellae, l’ancienne maison de la corporation des arbalétriers, située dans l’actuelle rue Baron Horta.

En 1772, coup d’éclat : la Bibliothèque s’ouvre enfin au public. Opération transparence avant l’heure.

En 1794 : Rebelote ! Les armées révolutionnaires françaises débarquent à Bruxelles et c’est reparti pour un tour. De nombreux manuscrits et livres précieux sont emportés à Paris par les agents du gouvernement français. Cette fois, nos trésors resteront en otage pendant plus de 20 ans. Ce n’est qu’en 1815, après la chute de Napoléon, que le Congrès de Vienne — cette grande réunion diplomatique où les puissances européennes redessinent les frontières et règlent les comptes — permettra de récupérer certains de nos ouvrages. Certains. Pas tous. Les négociations ont dû être épiques. Note pour l’histoire : piller le patrimoine culturel, ça a toujours été une stratégie de conquête. Aujourd’hui encore, on se bat pour que les œuvres volées retrouvent leur terre d’origine. Rien de nouveau sous le soleil.

En 1795, changement de statut : la Bibliothèque est rattachée à l’École centrale du département de la Dyle. Nouveau déménagement : direction les bâtiments de l’ancienne Cour, le Palais de Charles de Lorraine, place du Musée.

En 1803, nouvelle valse des propriétaires : la Bibliothèque est cédée à la Ville de Bruxelles.

En 1815, le gouvernement du Royaume des Pays-Bas — nos nouveaux occupants, après les Espagnols, les Autrichiens et les Français — décide de jouer à couper la poire en deux : la Bibliothèque est divisée. Les manuscrits redeviennent propriété de l’État sous le nom de Bibliothèque de Bourgogne ; la Ville garde les imprimés… jusqu’en 1842.

Le 19 juin 1837 : coup de génie. À l’occasion de l’achat par l’État belge de la collection du célèbre bibliophile gantois Charles Van Hulthem (70.000 volumes), le gouvernement crée officiellement la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique. Nom de code adopté.

Le 21 mai 1839, nouvelle ouverture au public dans l’aile gauche du palais de l’Industrie, adjoint au XIXe siècle au Palais de Charles de Lorraine.

Entre 1878 et 1881, extension du QG : une troisième aile de bâtiments est construite, reliant l’aile gauche du palais de l’Industrie à la rue du Musée.

En 1935, à la demande de la reine Élisabeth et du roi Léopold III, le gouvernement belge décide de construire une nouvelle bibliothèque à la mémoire du roi Albert Ier. Le bâtiment est conçu par l’architecte moderniste Maurice Houyoux.

En 1954, la première pierre de la Bibliothèque royale Albert Ier est posée par S.M. le roi Baudouin Ier.

Le 17 février 1969, inauguration solennelle du nouveau QG, l’imposante Bibliothèque Albert Ier à l’architecture brutaliste et à sécurité maximale.

En 2019, mutation identitaire : la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique évolue et devient KBR.

En 2020 : Opération transparence définitive. Ouverture du KBR museum. Après des siècles dans l’ombre, on expose enfin nos secrets et nos joyaux au grand public. La Librairie des ducs de Bourgogne, le noyau historique de la collection de KBR, est présentée au public à travers un parcours muséal original.

Mais pourquoi, je vous raconte tout ça ? Écrire un livre est une chose. Toutes les démarches qui suivent, c’en est une autre. Une fois le travail — de recherches, de rédaction, de mise page, de relectures multiples, de corrections, de re-relectures — fini, il y a une étape qui fait particulièrement sens pour constituer, protéger et préserver le patrimoine culturel.

KBR rassemble toutes les publications éditées en Belgique ou à l’étranger mais dont l’auteur•ice est belge et domicilié•e en Belgique. KBR les conserve pour les générations futures depuis l’institution du dépôt légal en 1966.

Le dépôt légal est une obligation. Mais derrière cette formalité administrative, il y a quelque chose de plus grand : des siècles de travail collectif, de patience, de transmission. Des gens qui ont choisi de protéger et de préserver. Une œuvre où l’humain et le sens ont leur place.

Merci à toutes celles et ceux qui font vivre KBR. Merci pour ce travail essentiel.

(Et si vous souhaitez commander le livre “Comment les coopératives créent de la prospérité pour toutes et tous” : https://tally.so/r/wAZYal )

KGB, KBR, FBI, MI6 — no, this is not the line-up of the latest James Bond film.

If, like me, you have extensive experience in secret services, three of these letters may have made you pause. KBR. But what on earth is that?

KBR is a close-protection service for humanity’s written treasures.

All right — those of the very small Kingdom of Belgium.

Brussels, capital of Belgium — hoofdstad van België, Hauptstadt von Belgien — is home to many jewels: a royal palace, certainly; a Grand Place unlike any other, carefully guarded by Saint Michael; countless bistros; the Comics Museum; a music conservatory in a sorry state; a Palace of Justice one would dearly like to preserve, in a world that seems to have lost its taste for it; fries, mussels, beers, chocolate — and a monumental library perched on the Mont des Arts.

But where do those three letters come from?

A Belgian history lesson: here, genres, languages and flavours are meant to mix.

“Historically, the name KBR is the contraction of two bilingual designations: Koninklijke Bibliotheek and Bibliothèque royale. In the past, it has borne many names: Albertine, La Royale, BR, KBR, KB, Bibliothèque royale, etc.”

(Excerpt from the KBR website: https://www.kbr.be/en/about-kbr/)

As so often in our modest kingdom, the Dukes of Burgundy and France are involved in everything. The story begins in the fifteenth century, when these noble figures had the bright idea of gathering some 900 precious works in order to dominate the world of knowledge — a mission of the ETERNAL MANUSCRIPTS kind. A unique collection of richly illuminated works.

Thus was born the Library of the Dukes of Burgundy, which held an inestimable treasure at the death of Philip the Good. You have guessed it: the former Library of the Dukes of Burgundy is medieval crème de la crème. Our hard core. Our Grail — still visible today, in the twenty-first century, at the KBR Museum. https://www.kbr.be/en/museum/

We could make a quantum leap here — but that would be a shame, as the plot thickens, rich in twists and turns, temptations of profit, and historical alliances and misalliances.

Philip II later gathered all the works in his possession at the Coudenberg Palace. From then on, the collection took the name Royal Library.

In 1731, a fire ravaged the Coudenberg Palace. Fortunately, our ancestors evacuated the manuscripts just in time. Well done, gentlemen.

In 1746, the French arrived and occupied Brussels. They “borrowed” our treasures and sent them to Paris. It would take until 1770 — twenty-four years later — for part of them to be returned. The others? Let us say we prefer not to dwell on that here, for fear of straining relations with Macron.

In 1754 came the first clandestine move: the collections found refuge in the Domus Isabellae, the former house of the crossbowmen’s guild, on what is now Baron Horta Street.

In 1772, a decisive move: the Library finally opened to the public. Transparency — ahead of its time.

In 1794, history repeated itself. Revolutionary French armies marched into Brussels, and off we went again. Numerous precious works were taken to Paris by agents of the French government. This time, the treasures would remain in captivity for more than twenty years. Only in 1815, after the fall of Napoleon, did the Congress of Vienna — the great diplomatic summit where European powers redrew borders and settled old scores— allow some of them to return. Some. Not all. The negotiations must have been epic.

A note for the record: looting cultural heritage has always been a strategy of conquest. Even today, battles continue so that stolen works may return to their land of origin. Nothing new under the sun.

In 1795, the Library changed status and was attached to the Central School of the Department of the Dyle. Another move followed, to the former Court buildings — the Palace of Charles of Lorraine — on Museum Square.

In 1803, ownership shifted once more, and the Library was transferred to the City of Brussels.

In 1815, the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands — our new occupants after the Spanish, the Austrians and the French — decided to split the difference. The manuscripts returned to state ownership under the name Library of Burgundy; the City kept the printed works… until 1842.

On 19 June 1837 came a stroke of genius: on the occasion of the Belgian State’s purchase of the collection of the Ghent bibliophile Charles Van Hulthem — some 70,000 volumes — the government officially created the Royal Library of Belgium. Code name adopted.

A new public opening followed in the left wing of the Palace of Industry, adjoining the Palace of Charles of Lorraine.

Further expansions came. New wings were built. In the twentieth century, at the request of Queen Elisabeth and King Leopold III, the Belgian government decided to construct a new library in memory of King Albert I. Designed by the modernist architect Maurice Houyoux, the building would eventually be inaugurated as a monumental, highly secured headquarters.

In 2019, the institution underwent an identity shift: the Royal Library of Belgium became KBR.

In 2020, the transparency operation was completed with the opening of the KBR Museum. After centuries in the shadows, secrets and treasures were finally revealed to the public. The Library of the Dukes of Burgundy — the historical core of KBR’s collections — is now presented through an original museographic parcours.

But why am I telling you all this?

Writing a book is one thing. Everything that follows is another. Once the work of research, writing, layout, multiple rounds of proofreading and correction is finished, one step remains that carries particular weight in the construction, protection and preservation of cultural heritage.

KBR gathers all publications issued in Belgium, or abroad, whose author is Belgian and resident in Belgium. Since the introduction of legal deposit in 1966, these works have been preserved for future generations.

Legal deposit is an obligation.

But behind this administrative formality lies something far greater: centuries of collective labour, patience and transmission. People who chose to protect and to preserve. A body of work in which humanity and meaning still have their place.

Thank you to all those who keep KBR alive.

Thank you for this essential work.

(If you want to order the book: How Do Cooperatives Build Prosperity for All? https://tally.so/r/w20YRM )

KGB, KBR, FBI, MI6 — nee, dit is niet de line-up van de nieuwste James Bondfilm.

Als je, net als ik, behoorlijk wat ervaring hebt met geheime diensten, dan zijn het vooral drie letters die even doen haperen. KBR. Wat is dat eigenlijk?

KBR is een beschermingsdienst voor het geschreven erfgoed van de mensheid.

Goed, dat van het piepkleine Koninkrijk België.

Brussel, hoofdstad van België — capitale de la Belgique, Hauptstadt von Belgien — zit vol schatten: een koninklijk paleis, uiteraard; een Grote Markt die uniek is in de wereld, scherp bewaakt door Sint-Michiel; ontelbare bistro’s; het Stripmuseum; een muziekconservatorium in erbarmelijke staat; een Justitiepaleis dat we koste wat kost overeind proberen te houden, in een wereld die daar steeds minder geduld voor lijkt te hebben; frietjes, mosselen, bier, chocolade — en een monumentale bibliotheek boven op de Kunstberg.

Maar waar komen die drie letters vandaan?

Een korte Belgische geschiedenisles: hier lopen genres, talen en smaken graag door elkaar.

“Historisch gezien is de naam KBR een samentrekking van twee tweetalige benamingen: Koninklijke Bibliotheek en Bibliothèque royale. In het verleden droeg de instelling tal van namen: Albertina, La Royale, BR, KBR, KB, Bibliothèque royale, enzovoort.”

(Uittreksel van de website van KBR : https://www.kbr.be/nl/over-kbr/)

Zoals zo vaak in ons bescheiden koninkrijk zijn de Bourgondische hertogen en Frankrijk overal bij betrokken. Het verhaal begint in de vijftiende eeuw, wanneer deze adellijke figuren op het idee komen om zo’n 900 kostbare werken samen te brengen om de wereld van de kennis te domineren — een missie van het type Eeuwige Manuscripten. Een unieke verzameling rijk verluchte werken.

Zo ontstaat de bibliotheek van de Bourgondische hertogen, die bij het overlijden van Filips de Goede een onschatbare schat bevat. De voormalige Bourgondische hertogelijke bibliotheek is middeleeuwse topklasse. Onze kern. Onze Graal — vandaag nog altijd te zien, in de eenentwintigste eeuw, in het KBR museum. (https://www.kbr.be/nl/museum/)

We zouden hier kunnen doorspoelen, maar dat zou jammer zijn. Het verhaal wordt net complexer, rijk aan wendingen, machtsdrang, allianties en breuken in de geschiedenis.

Filips II brengt later alle werken die hij bezit samen in het Coudenbergpaleis. Vanaf dan krijgt de collectie de naam Koninklijke Bibliotheek.

In 1731 gaat het grondig mis: een brand legt het Coudenbergpaleis in de as. De manuscripten worden net op tijd geëvacueerd. Op het nippertje. Goed gedaan, mannen.

In 1746 trekken de Fransen Brussel binnen. Ze “lenen” onze schatten en sturen ze richting Parijs. Pas in 1770 — vierentwintig jaar later — keert een deel ervan terug. De rest? Laten we het daar liever niet over hebben, om onze relaties met Macron niet onnodig te belasten.

In 1754 volgt een eerste clandestiene verhuis. De collecties vinden onderdak in de Domus Isabellae, het voormalige gildehuis van de kruisboogschutters, in de huidige Baron Hortastraat.

In 1772 gebeurt er iets nieuws: de bibliotheek opent haar deuren voor het publiek. Transparantie, nog voor iemand het zo zou noemen.

In 1794 herhaalt de geschiedenis zich. Revolutionaire Franse troepen trekken Brussel binnen en opnieuw verdwijnen kostbare werken richting Parijs, meegenomen door Franse staatsagenten. Ditmaal blijven ze meer dan twintig jaar weg. Pas in 1815, na de val van Napoleon, maakt het Congres van Wenen — die grote diplomatieke bijeenkomst waar de Europese grootmachten grenzen hertekenen en rekeningen vereffenen — het mogelijk een deel van de werken terug te halen.

Een deel. Niet alles. De onderhandelingen zullen niet zachtzinnig zijn geweest.

Een kanttekening voor de geschiedenisboeken: cultureel erfgoed plunderen is al eeuwenlang een vast onderdeel van veroveringspolitiek. Ook vandaag wordt die strijd nog gevoerd, wanneer geroofde werken hun weg naar huis proberen terug te vinden. Niets nieuws onder de zon.

In 1795 verandert het statuut van de bibliotheek en wordt ze verbonden aan de Centrale School van het departement van de Dijle. Opnieuw volgt een verhuis, dit keer naar het Paleis van Karel van Lotharingen, aan het Museumplein.

In 1803 komt de bibliotheek in handen van de Stad Brussel.

In 1815 beslist de regering van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden — onze nieuwe machthebbers na de Spanjaarden, Oostenrijkers en Fransen — om te splitsen. De manuscripten worden opnieuw staatseigendom onder de naam Bibliotheek van Bourgondië; de Stad houdt de gedrukte werken bij… tot 1842.

Op 19 juni 1837 volgt een sleutelmoment. Bij de aankoop door de Belgische Staat van de collectie van de Gentse bibliofiel Charles Van Hulthem — zo’n 70.000 volumes — wordt officieel de Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België opgericht. De naam ligt vast.

Daarna opent de bibliotheek opnieuw voor het publiek, in de linkervleugel van het Paleis der Nijverheid, aansluitend bij het Paleis van Karel van Lotharingen.

De instelling groeit. Nieuwe vleugels verrijzen. In de twintigste eeuw beslist de Belgische regering, op vraag van koningin Elisabeth en koning Leopold III, om een nieuwe bibliotheek te bouwen ter nagedachtenis van koning Albert I. Ontworpen door de modernistische architect Maurice Houyoux groeit het gebouw uit tot een monumentaal, zwaar beveiligd complex.

In 2019 verandert de instelling van naam en profiel: de Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België wordt KBR.

In 2020 volgt de definitieve omslag. Met de opening van het KBR museum worden eeuwenlang verborgen collecties zichtbaar. De bibliotheek van de Bourgondische hertogen — de historische kern van de KBR-collecties — krijgt er een eigen museaal parcours.

Maar waarom vertel ik dit allemaal?

Een boek schrijven is één ding. Alles wat daarna komt, is iets anders. Zodra het onderzoek, het schrijven, de vormgeving, het herlezen en corrigeren achter de rug zijn, blijft er een stap over die zwaar weegt voor het behoud van cultureel erfgoed.

KBR verzamelt alle publicaties die in België verschijnen, of in het buitenland, waarvan de auteur Belg is en in België woont. Sinds de invoering van het wettelijk depot in 1966 worden die werken bewaard voor wie na ons komt.

Het wettelijk depot is een verplichting.

Maar achter die administratieve handeling schuilt iets groters: eeuwen van collectief werk, geduld en overdracht. Mensen die ervoor kozen te bewaren, te beschermen en door te geven. Een plek waar betekenis en menselijkheid standhouden.

Dank aan iedereen die KBR meedraagt.

Dank voor dit onmisbare werk.

(Om het boek: “Coöperaties bouwen aan een betere wereld” te bestellen: https://tally.so/r/m6ozbY)